Is it myth or magic at work, for good or for ill?

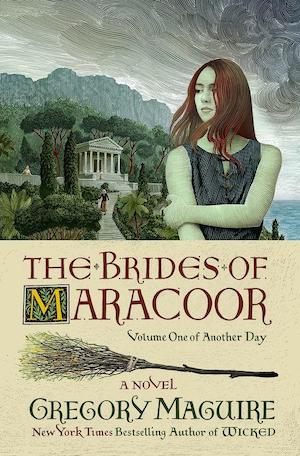

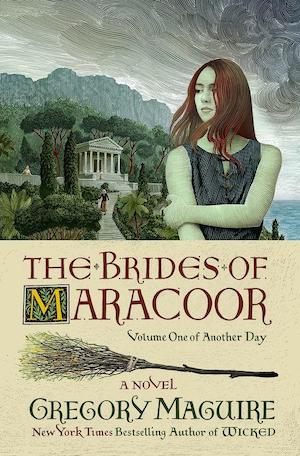

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Gregory Maguire’s The Brides of Maracoor, the first in a three-book series spun off the iconic Wicked Years, featuring Elphaba’s granddaughter, the green-skinned Rain. The Brides of Maracoor is available now from William Morrow.

Ten years ago this season, Gregory Maguire wrapped up the series he began with Wicked by giving us the fourth and final volume of the Wicked Years, his elegiac Out of Oz.

But “out of Oz” isn’t “gone for good.” Maguire’s new series, Another Day, is here, twenty-five years after Wicked first flew into our lives.

Volume one, The Brides of Maracoor, finds Elphaba’s granddaughter, Rain, washing ashore on a foreign island. Comatose from crashing into the sea, Rain is taken in by a community of single women committed to obscure devotional practices.

As the mainland of Maracoor sustains an assault by a foreign navy, the island’s civil-servant overseer struggles to understand how an alien arriving on the shores of Maracoor could threaten the stability and wellbeing of an entire nation. Is it myth or magic at work, for good or for ill?

The trilogy Another Day will follow this green-skinned girl from the island outpost into the unmapped badlands of Maracoor before she learns how, and becomes ready, to turn her broom homeward, back to her family and her lover, back to Oz, which—in its beauty, suffering, mystery, injustice, and possibility—reminds us all too clearly of the troubled yet sacred terrain of our own lives.

CHAPTER 1

Sing me, O Muse, the unheroic morning. When the bruised world begins to fracture for them all. Sing me the cloudless dawn that follows a downright shroud of a night.

A long night, one that had lasted for days.

Buy the Book

The Brides of Maracoor

Rain had run along the edge of it, playing for time.

Wind had sounded, then silence sounded—in that uncanny, hollow way that silence can sound. Then wind picked up again.

A world waiting to be made, or remade. As it does every night. Waves slapped the harbor sand with soft, wet hands.

At sea level, strokes of lightning silently pricked the horizon.

The seagrass bent double from wind and wet. Bent double and did not break.

Above the clouds—but who could see above the clouds?

Build the world, O Muse, one apprehension at a time. It’s all we can take.

With ritual dating from time out of mind, the brides on Maracoor Spot welcomed the first day after the storm. One by one they took up the whips of serrated seagrass from the basket in the portico. They wound the ends of the grass around their hands, using cloth mittens for protection. Each bride in her private nimbus of focus, they set to work etching their skin, laterally and crosswise. They flayed until the first drops of blood beaded up. Raw skin was better because it bled faster—the calluses from last week’s mutilations took longer to dig through.

Then the brides bound their bruises with muslin already dyed maroon. It cut down on the frequency of bridal laundering if the linen was a deadblood color to begin with.

***

CHAPTER 2

Then the brides—the seven of them—picked their way down the path along lengths of salt-scrubbed basalt. The ledge dropped in levels, finishing at a natural amphitheater shaped to the sandy harbor.

The world today, as they found it, as they preserved it:

A few thornbushes torn up and heaved on their sides, their leaves already going from green to corpse brown.

A smell of rot from fish that had been flung ashore in tidal surge and died three feet from safety.

The brides sat in a row on the lowest step. After chanting an in- troit, they began their work of twisting kelp with cord into lengths of loose netting. One by one each bride took a turn to wade into the calmed water up to her ankles, where the salt stung her daily wounds and cleansed them.

The oldest among them needed help getting up from a sitting position. She’d been a bride for seven decades or maybe eight, she’d lost count. She was chronically rheumy, and she panted like a fresh mackerel slapped on the gutting stone. Her stout thumbs were defter than those of her sister brides. She could finish her segment of the nets in half the time it took the youngest bride, who hadn’t started yet this morning because her eyes were still glossed with tears.

Acaciana—Cossy, more familiarly—was the youngest bride. She wouldn’t be menstrual for another year or two. Or three. So she cried at the sting of salt, so what?—she still had time to learn how to suffer. Some of the others thought her feeble, but perhaps they’d just forgotten how to be young.

Helia, Cossy, and the five others. Helia and Cossy, the oldest and youngest, wore white shifts that tended to show the dust. Only the oldest and youngest went bareheaded at tide weaving. Their hair, though pinned up close to the scalp, moistened in the insolent sun that came sauntering along without apology for its absence.

Beneath their sea-blue veils, the other brides kept their eyes on their work. Mirka. Tirr and Bray. Kliompte, Scyrilla. Their conversation wasn’t as guarded as their faces. Mirka, the second oldest, muttered, “I don’t think Helia is going to last another winter.”

“Netting for drama already?” murmured Tirr, the bride to her right. “And it’s just come summer.”

The others grunted.

“No, I mean it,” continued Mirka. “Look at the poor damaged old ox. She’s forgotten how to stand by herself. Those waves are almost too much for her.”

“Well, these storms,” piped up Cossy, trying to air a voice un- throttled by tears. “A whole week of it! Did that ever happen before?” The more seasoned brides didn’t answer the novice. The oldest woman did seem unsteady as she walked in. She’d looped her gar-ment in her forearms to keep the hems dry. Her mottled shanks trembled while the sea pulsed against her calves.

“What happens if Helia dies?” asked Cossy.

The youngest one always asked this question, always had to.

The second oldest, who was proud of the pale mustache that proved her status as deputy-in-readiness, snorted. “You remember the coracle that comes round the headland now and then. If it beaches and fewer than seven brides are here to greet the overseer, he goes back to procure a replacement bride.”

“Goes back where?” asked Cossy. “Mirka? Where?”

This question went unanswered. Since each new bride always appeared in swaddles, arriving before her own memory could set in, the notion of anyone’s specific origins was largely hypothetical.

Though they all knew where baby animals came from.

Cossy was at the obstinate age. “Goes back where? Someone must know. Does Helia know? I will ask her.”

“Don’t bother Helia,” said the deputy-in-readiness. “Look at her. At that venerable age! She’s about to move on ahead of us, she can’t think backward.”

“You’re not the boss of me, not yet,” Cossy replied. “And don’t think you are, Mirka.”

Helia had finished soaking her wounds. Using her staff for bal- ance, she picked her way back to her place. Once she’d taken up her portion of netting, she muttered, “I’m not as deaf as you think, Mirka. Don’t be getting airs. You’re not going to be senior bride anytime soon. Cossy, I don’t know much about the mainland but I know it exists, and it is where we come from. But listen: you can ask me anything you want. What little I know I share. That’s my last job before I die. All in good time, so Mirka, don’t go pushing me off a cliff.”

But that night at the temple Helia suffered some contortion, and the next morning, while she took breakfast, she didn’t speak at all. Cossy might ask all the questions she wanted, but to no avail. Helia was beyond answering.

From the book THE BRIDES OF MARACOOR by Gregory Maguire. Copyright © 2021 by Kiamo Ko Limited, LLC. On sale October 12 from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.